Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri, usually known only as Santa Maria degli Angeli, is an ancient Roman bath converted into a church in the 16th century. It is a minor basilica as well as being parochial, titular and formerly monastic.

It is on the Piazza della Repubblica, and near the Termini train station (itself named after the baths -Thermae not Terminus). Pictures of the church on Wikimedia Commons (an unusually good collection) are here. There is an English Wikipedia article here.

The dedication is to the Blessed Virgin Mary, as Queen of the angels and the Christian slaves who died building the Baths of Diocletian.

History[]

The Baths -History[]

There is an English Wikipedia article on the baths here. However, the Italian Wikipedia here article is better.

The Baths of Diocletian were the largest public baths in the city, and served the then heavily built-up areas of the Quirinal and Viminal hills. They were completed in 306 and, although dedicated to the emperor Diocletian , were actually commissioned by his imperial partner Maximian. However, they only had a useful lifetime of just over a century. The Sack of Rome in 410 probably saw the end of their daily use (although this is uncertain) and, like the other great baths of ancient Rome, they were completely abandoned as soon as the aqueducts collapsed in the 6th century. They were then used as a quarry. The internal decoration was extremely rich, with many columns of rare stone and much marble revetting, and this was a copious source of spolia for churches and palazzi.

However, elements of the complex managed to preserve their roofs throught the Middle Ages, notably the tepidarium and central frigidarium which together became the church, and also a rotunda on the north-west corner which became the church of San Bernardo alle Terme.

By the 16th century, the complex was covered in rampant vegetation, and was inhabited by many wild animals. As a result, the Roman nobility used it as a hunting preserve. The surrounding area was completely uninhabited at this time, as the medieval city stopped on the other side of the Quirinal. The site of the present nearby church of Santa Maria della Vittoria was occupied by a hermit who helped travellers caught by bad weather or threatened by robbers.

The neglect of the ruins came to an end in 1533, when Cardinal Jean du Bellay acquired the site, cleared the scrub and laid out gardens among the ruins. They hence became a tourist attraction possibly for the first time, and engravings of the period show visitors looking around.

Baths -Layout[]

The site of the baths has been encroached upon by later buildings, and is not easy to appreciate the original layout. However, a very useful plan of the original complex, and another of the surviving bits, are on the "mmdtkw" web-page in the "External links" below.

If you wish to experience the layout it is best to visit the Baths of Caracalla in the city first, which has a similar plan and has its ruins free-standing.

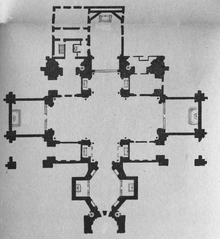

The first thing to remember is that when you are entering the church, you are actually going in the opposite direction to an ancient Roman entering the baths. The baths themselves occupied an enormous edifice with bilateral symmetry, on a transverse rectangular plan and with the major axis of symmetry running north-east to south-west. The baths were, in turn, surrounded by a vast rectangular enclosure, the entrance to which was on the north-east side. The opposite, south-west side had a huge semi-circular exedra, which is now followed by the buildings of the Piazza della Repubblica and which was flanked at the corners by two rotundas. The western one of these is now the church of San Bernardo.

After entering the courtyard the bather would have confronted by a façade, the middle of which concealed a large swimming pool or natatio. The apse of the church protrudes into the site of this. To either side were the two entrances, leading to changing rooms. Straight ahead of the entrances were two colonnaded courts or palaestras where he could work out (or she, on women's days). In between these two courts was the central part of the bath complex, at the middle of which was the frigidarium. This was the cold room, a vast hall located transversely to the major axis with three cross-vaulted bays marked out by eight monolithic granite columns. This is now the main part of the church. The other side of the frigidarium from the entrance façade led into the tepidarium or warm room, which is now the church's vestibule. Beyond that in turn was the caldarium or hot room, the heart of the whole complex. This has vanished, except for the apse connecting to the tepidarium which now has the church's entrance.

The present small side chapels between the vestibule and transept, and between transept and presbyterium, used to be entrances to four small roofed rooms containing cold plunge pools. There used to be a wide passageway leading from the frigidarium to the natatio, and this is now occupied by the presbyterium. The columns mentioned are of red granite, quarried at Aswan in the south of Egypt and taken by boat all the way down the Nile and across the sea to Rome. Doing so was an incredible undertaking.

Origin of the church[]

The remote origins of the church lie at Palermo in Sicily. A young Sicilian priest named Fr Antonio Lo Duca (born 1491) was choir-master of the cathedral when he discovered an ancient fresco of archangels in one of the city's churches. This gave him a lifelong devotion to the Seven Archangels (Michael, Gabriel, Raphael, Uriel, Raguel, Ramiel and Sariel) which are originally described in the Book of Enoch. After moving to Rome in 1527 to be chaplain of Cardinal Francisco Maria del Monte he began to campaign for the devotion to be liturgically honoured. However, Pope Paul III was not in favour and the major reason was that the devotion depended on the authority of a Jewish apocalyptic text.

In 1541 Fr Antonio was priest at Santa Maria di Loreto when he had a vision of the ruins of the baths and of seven martyrs who had allegedly died as slaves during its construction (named as Saturninus, Cyriac, Largus, Smaragdus, Sisinnius, Trasonius and Pope Marcellinus). This convinced him that the baths must be converted into a church, and he went there to paint the names of the archangels on seven of the eight granite columns. However, Pope Paul was still having none of it and it was only his successor, Pope Julius III, who agreed to the project.

A serious setback then occurred. The pope's nephews valued the baths as a base for hunting expeditions, and suggested to Fr Antonio that staying away was a very healthy idea. Papal nephews, however, used to lose their importance once a pope died. In 1560 Cardinal du Bellay died and bequeathed the baths to St Charles Borromeo, who passed them on to his uncle Pope Pius IV (1559-1565). The latter solemnly inaugurated the project in 1561. Doctrinal worries were allayed by having the new church dedicated to Our Lady only under the double title of Queen of Angels and Queen of Martyrs (the latter is an allusion to her Sorrows).

Michelangelo designed the church and started work in 1563, but after his death in 1564 (incidentally the same year that Fr Lo Duca died) his design was completed by his pupil Jacopo Lo Duca, also conveniently a nephew of Fr Lo Duca. The original layout involved the frigidarium being converted as it was found, with the entrance in the south-east short side and the high altar at the other, north-west end. Behind this altar was a subsidiary entrance that led to the road to the Porta Pia (the present Via 20 Settembre). The present end chapels of the transept were the entrance vestibules, formed out of ancient ancillary rooms in the baths. The present round vestibule led to a minor side entrance, while what is now the entrance to the presbyterium was a transept with the ancient passageway to the natatio walled up.

Carthusians[]

The church was a devotional exercise, and initially lacked a pastoral justification. So it was granted to the Carthusians on completion, who moved from their former monastery at Santa Croce in Gerusalemme. In doing so they abandoned a relatively newly built monastery, which hints at a problem for them there. Perhaps they found the administration of a famous pilgrimage basilica incompatible with their eremitic charism.

A story survives which claims that the baths had a link to the Carthusians centuries beforehand. St Bruno, their founder, had been called to Rome by Pope Urban II, his disciple, to be a papal adviser. The pope offered the saint the ruins of the baths as a place for a new monastery in 1091, but the saint was apparently not impressed.

The Carthusians immediately had a new monastery built adajcent to the church, possibly also to a design by Michelangelo although modern scholars now doubt this. The great cloister, around which are arranged the individual cells of the hermit monks, was built to the north-east of the church and did not respect the surviving ruins. To the south of this, next to the church, was built a much smaller cloister which also survives. However, adjacent ancient chambers to the north-east and the north-west of the eastern palaestra were incorporated into the monastic complex and are now part of the Museo Nazionale Romano.

The Italian word for a Carthusian monastery is certosa, and the English one is charterhouse. Both derive from the order's mother-house at La Grande Chartreuse.

Although the interior has been changed considerably and the floor has been raised by about two metres from the ancient level, this church is one of the places where you can best appreciate the size and splendour of the imperial baths as they were before their ruination.

In 1702, Pope Clement XI inaugurated a sundial on the floor of the church, the so-called Linea Clementina. It was designed by Francesco Bianchini, and its function was to check the validity of the new Gregorian calendar. This was especially important as regards the date of the Spring Equinox, since the date of Easter depended on it.

Vanvitelli's restoration[]

In 1749, major alterations to the church were decided upon by the monks and carried out by Luigi Vanvitelli as the main architect in preparation for the Holy Year of 1750. Beforehand, the main entrance was on the short south-east side of the frigidarium, which was hence the nave. Vanvitelli transferred the entrance to the long south-west side, turning the subsidiary side entrance into the main entrance. The two entrance vestibules were turned into side chapels (this part of the scheme slightly pre-dated Vanvitelli's work), and the entrances blocked up by the new chapel altars. He then demolished Michelangelo's blocking wall opposite the new main entrance, and made a presbyterium out of the passageway to the natatio. Finally, he knocked a hole in the ancient screen wall on the south-west side of the natatio in order to add an apsidal choir which intruded into the natatio and touched the small cloister.

This arrangement left the church with an enormous and disproportionate transept , and architectural historians have puzzled as to why the Carthusians undertook such an odd and unsatisfactory alteration. Very few writers have had anything good to say about the result, and contemporaries were hostile at the demolition it entailed. Especially serious was the clearing of the ruins of the caldarium in order to build a Baroque entrance façade which had clustered pilasters and a triangular pediment.

The Nolli map, contemporary with the new work, shows the great cloister with seven cells which would have meant that the Carthusian community was a small one. They only occupied one side of the cloister, to the north-west. An enormous piazza, the Piazza delle Termini, ran along the south-east, south-west and part of the north-west sides of the monastery and the Pope used to muster his soliders there in times of trouble. Back then, the exedra of the baths was part of the gardens of the Cistercian monastery of San Bernardo.

Modern times[]

After the unification of Italy in 1870 the Carthusians were evicted from their monastery, which for some time was used as a military barracks. Then it housed the major collection of the Museo Nazionale Romano, but this has now been moved to the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, leaving behind an enormous collection of epigraphs which is housed in modern halls as part of the Museo Nazionale delle Terme. Visitors to this are also able to view the monastic cloisters.

The church was eventually handed over to the Order of Minims for a period. In 1896, the wedding of the Prince of Naples, later King Victor Emmanuel III, raised the status of the church. It has since been the scene of religious ceremonies promoted by the Italian State.

The church became titular only in 1906, when it was made parochial. The parish territory was transferred from San Bernardo.

The church was given the status of minor basilica by Pope Benedict XV in 1920. Later it had a restoration which entailed the demolition of Vanvitelli's façade in order to reveal the surviving fabric of the caldarium. Today it is served by diocesan clergy, and remains a parish church.

The parish has established a respectable musical profile. A very good organ was inaugurated in 2000, and there is a noted schola cantorum or choir.

Cardinalate[]

The previous titular of this church was William Henry Keeler, Archbishop of Baltimore . He died in 2017, leaving the title vacant for a short period before the appointment of Anders Arborelius in the same year.

Exterior[]

Layout and fabric[]

The exterior is unique for a church, as the outer walls of the Baths of Diocletian are partially preserved in the overall complex. On the other hand, the church has no civic presence as such since the 16th century Baroque façade was demolished in the 20th century to expose the surviving wall of the caldarium.

Looking at the church from the south, you may be confused as you will be presented with a hulking mass of red brick masonry which looks rather shapeless. However, the nearest block of buildings belong mostly to the museum not the church. Above this you will see a large three-light window with a shallow curved top and two thick brick mullions . This is the narrow gable end of the transept, and here used to be the original entrance. The transept itself stretches along behind the separate vestibule (the former tepidarium) which has a low tiled octagonal dome. This longitudinal roofline of the transept has three gables over windows of the same style as that mentioned, although the outer pair only have single lights. There is a large round-headed window to the right of the vestibule.

The end chapels of the transept, added in the Vanvitelli restoration and made out of ancient rooms that Michelangelo utilized as entrance vestibules, have lower roofs and are narrower than the transept itself. They are on an indentically sized square plan. The south-eastern one is surrounded by museum premises, while the north-western one can be seen from the Via Cernaia (it is recommended that you take the trouble to walk round to look at the church from this angle, as you can also see the Carthusian cells).

There is a campanile, not easily visible from the street. It is just to the left of the far left hand corner of the main apse, and has an unusual L-shaped plan formed of two slab walls with Baroque scrolling on top. Each wall has two round-headed bell apertures, one above the other.

Façade[]

What now passes for the façade is a concave fragment of wall of the former caldarium, which is a mess although it is impressively thick brickwork. A modern skin of brick covers the central part of this, and this contains two identical round-headed portals separated by a round-headed niche which looks as if it should have a statue but only contains a worn antique column capital. The church's name is above the portal, just to let passers-by know that it is there.

Bronze doors[]

The two bronze entrance doors are important works of modern sculpture by the Polish artist Igor Mitoraj, and were completed in 2005. The left door depicts the Resurrection, while the right door depicts the Annunciation. Most of the surfaces of both doors are blank, showing textured and patinated metal, but out of the surfaces emerge dismembered figures and heads as if they were floating in water. The three figures of Christ, Our Lady and the Archangel Gabriel have arms amputated, and this detail is an allusion to the damaged Classical statues that used to be displayed in the adjacent museum. The figure of Christ is further divided into four by two slashes in the form of a cross.

On the insides of both doors are large figures of Archangels.

Certosa[]

If you do walk around to Via Cernaia, you can look down into the remains of the Certosa or Carthusian monastery. Here you can see the backs of the self-contained

Church from the north-west.

cells used by the Carthusian hermit monks, each with its little garden separated from its neighbours by a high wall. On the other side of these cells is the north-west walk of the great cloister.

The Museo Nazionale delle Terme, an excellent archaeological musuem, is located in another part of the baths and visiting this allows one access to this cloister. The arcades are 80m long on each side, with a total of a hundred travertine columns. The original pale blue colour was brought back in a restoration in 2000. The garden is a peaceful place, and contains a fountain of 1695 incorporating ancient carvings of animal heads. One of the cypress trees growing here may have been planted when the monastery was founded.

Piazza della Repubblica[]

The major axis of the church continues as the axis of symmetry across the Piazza della Repubblica , and down the Via Nazionale. Thus the church is the focus of an important part of the modern city's layout, and hence it is even more of a pity that it does not have its own monumental entrance façade.

The circle of the Piazza is produced by taking the curve of the exedra of the baths, and completing the circle of which it is an arc. The new road layout was put in place in 1887, and the symmetrical arcaded buildings following the exedra arc were completed in 1898. The architect was Gaetano Koch.

Before 1960, the piazza was called the Piazza dell'Esedra.

Fontana delle Naiadi[]

In the decades before 1870 Pope Pius IX was making some effort to modernize the city's infrastructure, although this was a rather hesitant undertaking. Specifically, he began the process of making the new train station at Termini, under construction since 1868, the focus of a new transport network. Part of the preparation for the new suburban expansion hence expected around the church was the provision of a water supply, and this was done by a new private water company called the Acqua Pia restoring part an ancient aqueduct called the Aqua Marcia. The terminal fountain for this new supply was very near the present fountain, which was moved when the Piazza dell'Esedra was laid out in order to put it on the major axis of the church.

The original papal fountain was undecorated. The new fountain after 1887 was decorated with very cheap sculptures of lions, which proved unsatisfactory. So, in 1901 the city commissioned a new decorative scheme by the Sicilian sculptor Mario Rutelli. He provided four naiads in bronze, subduing aquatic creatures, and (later) a central figure of a water-god. The naiads proved a problem. They are nude female figures, obviously sculpted from life with properly defined nipples as well as incipient bunions -not in the Classical tradition. The models were twin music-hall performers. The resultant fountain seriously offended some local Catholics as well as expatriates, and pilgrim guidebooks before the First World War warned visitors to the church against it. Chandlery 1902 wrote this:

"In the piazza in front of the church is a large fountain, where the municipality of Rome erected in 1901 some bronze figures that are repulsive and scandalous in the extreme. No good Christian would look at them, and even a pagan with any self-respect would turn away disgusted".

Be that as it may, the fountain was admired by Mussolini , is now regarded as one of the few major works of the Art Nouveau at Rome and is described by a contemporary guidebook (the "Blue Guide") as "faintly erotic". Times change.

There is a charming story that the twin girls concerned used to visit the fountain regularly as old ladies, to remind themselves of the days when they were young and beautiful. The sculptor travelled from Sicily once a year for as long as he was able, to treat them to a meal at Rome.

Interior[]

Vestibule[]

When you go through the bronze entrance doors, you find yourself in a short and wide corridor. This was a passage hall in the Baths, between the caldarium (the hot bath, now mostly lost) and the tepidarium (luke-warm bath).

The latter is now the vestibule, although Michelangelo had it as a side annexe with a subsidiary entrance. It is circular, with a projecting chapel on each side. To the left is the Chapel of St Mary Magdalen, which is also the baptistery, and to the right is the Chapel of the Crucifix.

The dome is coffered with rosettes, and its oculus contains an important modern piece of stained glass entitled Light and Time by Narcissus Quagliata and inaugurated in 1999. Both Michelangelo and Vanvitelli had installed lanterns for the dome, but both failed structurally and the 20th century skylight that replaced it also let in the rain. The present work has the shape of a segment of a sphere about 3 metres across, and has a sunburst motif in white, black, yellow and several shades of blue. The design is divided into eight sectors by black radii, and these radiate from a central yellow disc representing the sun through a white zone to an outer blue zone. The glasswork contains three prismatic lenses designed by the Mexican astronomer Salvador Cuervas, and these focus an image of the sun on the floor below on the days of the equinoxes (together) and the two solstices. The glass cupola is not attached to the ancient roof fabric, but rests on three gilded steel spheres and thus leaves a narrow gap all round for ventilation.

Michelangelo added four pedimented niches to the walls between the chapels and main passageways, and these are all now occupied by funerary monuments. The description below is anticlockwise from the entrance.

The first niche. The artist Carlo Maratta (1625–1713), responsible for the Chapel of St Bruno and the painting of The Baptism of Jesus, is buried here. He designed the funerary monument himself, and it may have been erected by his brother Francesco. The brother definitely carved the marble bust on the monument, which is just to the right as you enter the vestibule.

The Chapel of the Crucifix was built in 1575 for the Roman banker Girolamo Ceuli. The altarpiece, depicting The Crucifixion, is attributed to Giacomo della Rocca, a pupil of Daniele da Volterra. The same artist decorated parts of the walls and vault with frescoes, which unfortunately were badly restored in 1838. The sculptor Pietro Tenerani (died 1869) is buried on the left side of the chapel. The monument has a bust of the artist, and a door which symbolizes the entrance to Hades, the Land of the Dead. A small funerary monument to his wife, Lilla Montebbio, is placed in the opposite wall.

The second niche. The tomb of Cardinal Francesco Alciati (died 1580) was erected in 1583 and is to the left of the Chapel of the Crucifix. It was made by either Jacopo Lo Duca or by Giambattista della Porta. Cardinal Alciati was a protector of the Carthusian order, and the monks honoured him by burying him in their Roman church even though he was from Milan.

The third niche. The tomb of Cardinal Pietro Paolo Parisi was erected in 1604 by the Cardinal's nephew, Bishop Flaminio of Bitonto.

The Magdalene Chapel is the baptistery of the church. It was constructed in 1579, and paid for by Consalvo Alvaro di Giovanni. The altarpiece with Noli Me Tangere is attributed to Cesare Nebbia by some, and by others to Arrigo Paludano. It depicts the meeting of Jesus Christ and St Mary Magdalene after the Resurrection, when he asked her not to touch him ("Noli me tangere"; John 20,1).

The fourth niche. The artist Salvator Rosa is interred in a monument contructed by his son in 1673 and sculpted by Bernardino Fioriti.

In general, the background decorative elements of the vestibule and passageways are by Vanvitelli.

In 2000 a new bronze sculpture by Ernesto Lamagna was placed in the vestibule. It depicts the Angel of Light, and is described as "futuristic Baroque". A rather etiolated, insectile angel in patinated bronze is shown flying over a black stone pyramid; the artist used corrosive acids to produce the patina. He was inspired by the practice of Michelangelo of burying his bronze sculpture in fresh excreta and leaving them to stew for months, in order to have them ending up looking antique and hence having added value.

Pronaos to transept[]

In Michelangelo's design, this was the left arm of the transept when what is now the transept was the main body of the church. It was rearranged by Vanvitelli, who added four columns in plaster-covered brick painted to look like granite. These support a continuation of the entablature that runs all the way round the transept, except for the end chapels and presbyterium, and incorporates this architectural space into that of the present transept as a whole. What it could be descibed as is a very short nave or pronaos.

The roof has a short and shallow barrel vault, which looks as if it is coffered in octagons and small squares, with rosettes. This is merely painted. There are two side chapels, that of St Peter on the left and that of St Bruno of Cologne (1035–1101), founder of the Carthusians, on the right. Oddly, St Bruno has two chapels in this church; this is the little one, and the big one is at the north-west end of the transept. The chapels used to be passageways to two identical ancient rooms containing cold plunge pools.

On the wall above the entrance from the vestibule is the painting The Banishment from Earthly Paradise by Francesco Trevisani. This is the last painting made by the artist, who died in 1746. It is set in an elliptical tondo, which breaks into the entablature, and shows God the Father enthroned on a cloud and overseeing the expulsion of Adam and Eve from Eden. They are running away in the background.

The holy water stoup on the right, which is held by a beautiful angel, is attributed to Giambattista Rossi who was a pupil of Bernini. The matching one on the left is by Vanvitelli, of course. It was provided when the main entrance was moved to here.

In a niche above the stoup on the right there is a statue of St Bruno (1035–1101), sculpted by Jean Antoine Houdon between 1766 and 1768. Pope Clement XIV is reputed to have said that the statue was so lifelike that it would have spoken if the order had not forbidden it (the Carthusians take a vow of silence for six days a week; Thursday is community walk day, when they are expected to socialize). His head is bowed in humility and thoughtfulness, and the statue is placed so that the saint is turned towards the centre of the apse. The niche opposite used to have a stucco statue of St John the Baptist but this was destroyed in 1894. It is proposed to replace this by a work on the same subject by by Giuseppe Ducrot.

The Chapel of St Bruno was built in 1620 and paid for by the Polish Monsignor Bartolomeo Povusinski. The altarpiece, by an unknown artist of the 17th century, depicts the saint. Vanvitelli added the monumental entrance, imitating the style of Michelangelo as demonstrated by the tomb niches in the vestibule.

The Chapel of St Peter (the full dedication is to God the Father and St Peter) was constructed in 1635 at the expense of Pietro Alfonso Avignonese. The façade is by Vanvitelli again. The altarpiece is The Delivery of the Keys by Girolamo Muziano, and is an extremely fine work as is the altar frontal in pietra dura. He is also thought to be responsible for the fresco on the vault, showing God the Father. On the left wall is a painting St Peter Freed by an Angel, and on the right wall SS Peter and Paul; both of these are by Marco Carloni, who was a local Roman artist of the 18th century.

In this chapel is a modern marble sculpture, the Head of John the Baptist by Igor Mitoraj. Donated by the artist, this is a naturalistic neo-Classical work showing the saint's head after his beheading.

Transept - general[]

The transept is basically the enormous frigidarium or cold room of the baths. It should be noted here that the term frigidarium properly describes a room with a cold plunge pool, and this room did not have one. Rather, the ancient layout had four plunge pools in adjacent small rooms. Hence, some descriptions of the baths prefer the terms basilica or "central hall" for this space. It was first adapted by Michelangelo, who found it with its ancient vault substantially intact, and was then altered by Lo Duca and Vanvitelli. The ancient cross vault is 29 metres high. The eight original granite Corinthian columns are 17.14 metres high, including bases and capitals, and have a diameter of 1.62 metres. They originally had plinths 2 metres high, but these were covered over when Michelangelo raised the floor level. Some writers have alleged that this ruined the proportions of the architectural space, which is true according to the ideals of Vitruvius.

As mentioned, Vanvitelli extended the entablature above these ancient columns to run all round the pronaos just described, and also the corresponding pronaos of the presbyterium. To support the entablature in these two pronaotes, he added eight further columns (four in each place) which look like granite but are imitations in brick covered with stucco. If you get confused as to which columns are granite and which are brick, touch them. The granite ones are cold.

The walls have pilasters in imitation red marble, a matching red frieze in the entablature, and enormous round-headed panels. These house eight large paintings most of which were originally in San Pietro in Vaticano, and were moved here in the 18th century. See below for individual descriptions. There is a large three-light window over each of the two triumphal arches into the end chapels, and these arches themselves have shallow arcs. They are matched by the arches into the entrance pronaos and the presbyterium pronaos, which are the ends of their barrel vaults. Over the two latter are another two three-light windows, and a further pair of single-light windows flank each one of these. The three-light window over the entrance archway is decorated with volutes which incurve attractively at the bottom, and the one over the presbyterium pronaos has angels sitting on the arc. All this decoration is by Vanvitelli.

As noted, much of what looks like polychrome marble work in the transept's decorative scheme is actually painted stucco. This indicates that the Carthusians had trouble paying for the Vanvitelli restoration. Further, the vault of the transept is undecorated, being simply whitewashed, which hints that the scheme was abandoned before completion. The lunettes have frescoes by Niccolò Ricciolini, who also decorated the Cybo Chapel.

Meridian[]

The floor was laid in the 18th century by Giuseppe Barbieri. The sundial in it was made by the astronomer, mathematician, archaeologist, historian and philosopher Francesco Bianchini. Bianchini had been commissioned by Pope Clement XI to make it for the Holy Year of 1700. It took a bit longer; it was completed in 1703 with the assistance of the astronomer Giacomo Filippo Maraldi. Then it provided the standard for local Roman time until 1846, when it was replaced by a cannon being fired at noon from the Janiculum. This was controlled by an accurate chronometer.

Bianchini's sundial was built along the meridian that crosses Rome, at longitude 12° 30' E. At solar noon, which varies according to the equation of time from around 10:54 a.m. UTC in late October to 11.24 a.m. UTC in February (11:54 to 12:24 CET),[2] the sun shines through a small hole in the wall to cast its light on this line each day. At the summer solstice, the sun appears highest, and its ray hits the meridian line at the point closest to the wall. At the winter solstice, the ray crosses the line at the point furthest from the wall. At either equinox, the sun touches the line between the these two extremes. The longer the meridian line, the more accurately the observer can calculate the length of the year. The meridian line built here is 45 meters long and is composed ofbronze, enclosed in yellow-white marble.

In addition to using the line to measure the sun's meridian crossing, Bianchini also added holes in the ceiling to mark the passage of stars. Inside the interior, darkened by covering the windows, Polaris, Arcturus and Sirius were observed through these holes with the aid of a telescope to determine their right ascensions and declinations.

If you look at the right side of the transept wall, you can see that part of the cornice has been cut away to allow entrance to the sun's rays.

On the floor around the sundial are several panels portraying signs of the zodiac.

Transept - left arm[]

Three of the great paintings from St Peter's are here. They are taken in anticlockwise order, right to left when facing the chapel.

The Immaculate was painted by Pietro Bianchi in the early 18th century. It was made for the altar in the Chapel of the Choir in St Peter's, and brought here after a mosaic replica was provided. In it, Our Lady surrounded by angels and putti is being pointed out to SS Francis of Assisi and Anthony of Padua by St Gregory Nazianzen.

Placido Costanzi painted The Resurrection of Tabitha. It was originally made for the altar of Tabitha in St Peter's, where again it has been replaced by a mosaic copy. The painting shows Tabitha of Joppa being brought back for the dead by St Peter (Acts 9, 36).

The Fall of Simon the Sorcerer by Pompeo Batoni, painted in 1765, is one of two paintings with this subject in the church. The painting depicts the legend of Simon Magus, who challenged SS Peter and Paul to a thaumaturgy contest at Rome. He levitated in front of them, asking them to demonstrate whether their god was as strong in power. The Apostles prayed, and Simon plummeted to his death. The story derives from an apocryphal work called the Acta of SS Peter and Paul. This painting did not come from St Peter's.

The Mass of St Basil by Pierre-Hubert Subleyras was painted in 1745 for the altar of St Basil in St Peter's. The Eastern Doctor of the Church is shown celebrating Mass before Emperor Valens, who was an Arian heretic. The saint's devotion was so strong that the Emperor fainted, and later converted to Orthodox Christianity. The event is unhistorical, although it is true that St Basil had such a strong power-base in what is now central Turkey that the emperor did not dare to molest him.

Chapel of St Bruno[]

The new Chapel of St Bruno was constructed as part of the restoration works for the 1700 Jubilee, and has a roof lower than that of the main transept. The prior of the Carthusian charterhouse, Fr. G.M. Roccaforte, had decided to turn the former back entrance hall of the church into a chapel dedicated to the founder of his order which was much larger and grander than the one already existing. It was designed by Carlo Maratta, and apparently contains a magnificent altar canopy supported by four columns of serpentine. This is a trompe d'oeil, being merely painted on the wall, as are the apparent stucco decorations to each side.

The altar itself was made from bits of an older altar, and was constructed by Francesco Fontana in 1864. It contains fine polychrome stonework.

The altarpiece is The Apparition of the Virgin Mary to St Bruno by Giovanni Odazzi. It was painted for the 1700 Jubilee, and shows the Blessed Virgin handing the Order's Rule to St Bruno. The vault was painted by Andrea Procaccini with figures of the Evangelists, while the rest of the decorations were painted by Antonio Bicchierai. The sculptures to the right of the altar depict The Meditation (1874) and The Prayer (1875), and are stucco copies of statues at the entrance to the Verano cemetery near San Lorenzo fuori le Mura, by Francesco Fabi-Altini. The former statue used to be on the left hand side of the altar, but was moved when the organ was installed.

Francesco Trevisani used to have two matching paintings on the side walls of this chapel; he also painted two works in the other arm. The two here used to be a diptych called The Baptism of Blood, and refer to the Catholic belief that an unbaptised person who dies for the Faith is baptised through the shedding of his or her blood. When the organ was installed one of the pair was moved to a resources room located behind the right hand wall of the chapel; this space, not accessible directly from the church, used to be the Chapel of St Teresa of Avila. They were painted on boards, not canvas.

Organ[]

On the left wall on the Chapel of St Bruno is now the monumental organ, built by Bartélémy Formentelli in the 1990's and inaugurated in 2000. It has 77 registers distributed on four keyboards, and is made using cherry, walnut and chestnut wood. There are 5400 hand-made pipes, and the instrument is claimed to be the only one in Europe demonstrating the consolidation of the French and Italian organ-building styles. It is often used for concerts, being one of the best in any parish church in Rome.

Transept - right arm[]

The artworks are described in anticlockwise order, starting at the right-hand side when facing the chapel.

The Crucifixion of St Peter is by Nicola Ricciolini (1687-1760), and is a copy of a work by Il Passignano. It comes from St Peter's.

The 18th century painting The Fall of Simon the Sorcerer (see above for background information), by Pierre-Charles Trémollière, is a copy of a 16th century painting by Francesco Vanni now over the altar of the Sacred Heart in St Peter's.

Over on the left hand side is the tomb of General Armando Diaz, an Italian hero of the First World War. This was made by Antonio Muñoz in 1920. The sarcophagus is of red granite from Aswan in Egypt, matching the ancient columns, and is placed in the transept floor. The monument itself rises above that. In the centre is a dedication stele flanked by two slabs of African green marble with bronze decorations in the shape of swords with laurel crowns.

Above the monument is a painting showing A Miracle of St Peter by Francesco Mancini. It was probably first placed in the Quirinal Palace, and shows the healing of a leper. A mosaic copy has been made for St Peter's.

The Sermon of St Jerome, late 16th century, by Girolamo Muziano was left unfinished by the painter at his death in 1592. Paul Brill completed it by painting in the background. It was originally made for St Jerome's altar in St Peter's, but was moved here.

Chapel of Bl Niccolò Albergati[]

The chapel of Blessed Niccolò Albergati has the same plan as that of St Bruno on the opposite side, and again is part of the Vanvitelli restoration. It was designed by Clemente Orlandi in 1746 and formed out of the church's former main entrance vestibule. The dedication is to a Carthusian monk who had become a cardinal, and an important Church diplomat in the early 15th century. He had been beatified by Pope Benedict XIV in 1744; there are very few saints and beati in the Carthusian order, because (in stark contrast to other religious orders) they have never promoted the canonization of their members.

The trompe l'oeil painting of a richly decorated altar canopy matches that in the chapel of St Bruno opposite.

The cross vault was decorated by Antonio Bicchierai (1688-1766) and Giovanni Mozetti. In the middle of the vault is the Holy Spirit with cherubs, and in the panels are the four Western Doctors of the Church: SS Jerome, Augustine, Ambrose and Gregory. This work gives a hint of what the main vault may have looked like if the Carthusians had not run out of money.

The altarpiece depicts A Miracle by Blessed Niccolò Albergati, and was painted by Ercole Graziani in about 1746. Flanking the altar are two statues by the German sculptor Friedrich Pettrich, made in 1834, depicting The Angels of Peace and Justice.

The side walls of the chapel have two interesting tombs. The tomb of Vittorio Emanuele Orlando, on the right side, was made in 1935 by Pietro Canonica, a Piemontese sculptor. Orlando is known in Italy as Presidente della Vittoria (President of the Victory) in the First World War. The sarcophagus is in yellow Sienese marble with a bronze medallion. There is a relief on the Carrara marble base. An arch stretches above the sarcophagus, symbolizing fame and glory. Those from abroad often forget that the Italian Campaign of the First World War against the Austro-Hungarian Empire was both vicious and deadly.

Opposite this tomb is the one of Admiral Paolo Thaon di Revel , known as the Duca del Mare (Duke of the Sea). This too was made by Canonica, in 1948. The sarcophagus is made in the same type of stone, and the monument is likewise crowned with an arch. The shape is different however, as it is carved to resemble a rostrated ship, fitting for the Admiral. The base is in red Levantine and black Belgian stone. In the centre of the base is a relief portrait in a clipeus.

On the side walls, above the funarary monuments, are the two paintings Baptism of Water and Baptism of Desire by Francesco Trevisani, painted in the 18th century. They form a set with the two works on the Baptism of Blood formerly in the chapel opposite. The Baptism of Desire refers to a concept in the Catholic understanding of baptism. Cathecumens who die before they can be baptised are considered as having received the grace of baptism through their desire for the Sacrament.

Pronaos of the presbyterium[]

This architectural space was the right arm of the transept in Michelangelo's design, and was decorated by Vanvitelli in the same way as the corresponding entrance pronaos opposite. Hence, it has four plastered brick columns looking like granite which support a continuation of the entablature of the main transept, and above which is a shallow and short barrel vault with false coffering. Also it has two flanking chapels, that of St Hyacinth on the right and the Saviour on the left. In ancient times these led to two rooms with cold plunge pools.

The Chapel of St Hyacinth (Cappella di San Giacinto) was founded by Allessandro Litta, a Milanese nobleman, in 1608. He had it dedicated to Our Lady and St Hyacinth. The altarpiece was painted by Giovanni Baglione. It depicts The Virgin with the Child and Angels, St Raymond and St Hyacinth. On the right side of the chapel are depicted SS Valerian and Cecilia, and on the left Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata, both by Baglione. He also painted the frescoes of God the Father with Angels on the vault. "Raymond" is Raymond of Peñafort, and "Valerian and Cecilia" are the Roman martyr Cecilia and her husband.

The Chapel of the Saviour is the oldest in the church, founded in 1574 by the De Cinque family. Later the Catalani family became patrons of the chapels, and a member of that family wrote a book about the construction of the church in the 17th century, providing important information about its history. On the right wall, a marble epigraph informs us about an indulgence granted by Pope Gregory XIII to the followers of the Confraternity of the Seven Angels. The altarpiece depicts The Incarnation of Jesus and The Adoration of the Seven Angels, by Domenico da Modena. It is surrounded by 24 small paintings of scenes from the life of Our Saviour, attributed to the 16th century artist Hendrik van der Brock (known in Italian as Arrigo Fiammingo). It is certain that van der Brock decorated the ceiling in the chapel with depictions of Our Lord and St Michael the Archangel. On the side walls are Giulio Mazzoni's The Souls in Purgatory and The Praying Pope, painted in the 16th century. The characters in the latter painting are all connected to the founding of the church; we find Pope Pius IV, Cardinal Serbolloni, Emperor Charles V, Antonio Lo Duca and many more.

Presbyterium and apse[]

The presbyterium is entered under a triumphal arch, formed because its barrel vault is lower than that of its pronaos. Over the arch is an inscription Reginae angelorum et martyrum (To the Queen of angels and martyrs), carved as if on a billowing banner -a very Baroque motif. This arch was previously occupied by a blocking wall built by Michelangelo, which was removed in the Vanvitelli restoration.

The presbyterium itself was designed by Clemente Orlandi on the occasion of the arrival of the first of the large paintings from St Peter's; he also designed the chapels at the ends of the transept. The choir stalls in the apse and the background decorations overall were made by Vanvitelli. He also altered the plan, so that the presbyterium was given a polygonal apse, and made a new high altar which was against the apse wall. The far end of the presbyterium forms a sanctuary which is approached by a flight of four steps. At the top of these is a balustraded screen in veined red marble, which is matched by the stonework of the altar itself just behind it. The apse has three windows separated by large decorative brackets, and now contains the choir stalls of the monks.

The provision of an apse required the mutilation of the ancient screen wall of the natatio in order to make way for its vault. If you walk into the apse and get transported in time back to ancient days, you would find yourself in a swimming pool.

The layout was altered again, more or less to its present state, in 1867. The Carthusians brought the high altar forward, re-arranged the choir stalls behind it and provided them with an open metal screen in front. This was motivated by the wish to define the monastic enclosure more clearly, but unfortunately the monks only had six years to enjoy the re-arrangement. This metal barrier has four openwork panels decorated with the initials of the Carthusian Order, surrounded by the seven golden stars which is their emblem. The double gates in between the panels have their swinging barriers in the shape of harps. This screen was designed by Angelo Santini, and the ornaments by Giuseppe della Riccia.

Flanking the altar are two sculptures by Innocenzo Orlandi, dated 1866: The Angel with an Eagle and The Throne, the latter of which is placed upon a bull and a lion. These four elements are the symbols of the four Evangelists.

A new bronze pulpit was inaugurated in 2009. It is an important work of art by Giuseppe Gallo, and depicts the crucified Christ taken down from the Cross. The whole pulpit is intended to symbolize the Tomb from which the Resurrection is announced.

On the right wall of the presbyterium in front of the sanctuary is Giovanni Francesco Romanelli's The Presentation of the Virgin Mary at the Temple. The Baroque work recalls the episode when the Blessed Virgin, as a child, was taken to the temple by her parents, St Joachim and St Anne, to be consecrated to the Lord. Mary is shown as a little girl climbing the steps alone to present herself to the high priest.

Next to this and nearer the sanctuary is The Martyrdom of St Sebastian by Domenichino. It was made for the altar of St Sebastian in St Peter's. The horseman on the right was damaged when it was transferred here. In the dramatic painting, Jesus Christ is welcoming the saint while an angel comes down with the palm and crown of martyrdom.

Either side of the apse there are two doors surmounted by busts, one on each side of the choir stalls (the right hand one is now blocked). One bust is of St Charles Borromeo who briefly owned the ruins, and the other is of Pope Pius IV.

In the apse itself are two memorial tablets, to Pope Pius IV and Cardinal Fabrizio Serbelloni, the first titular of the church. In the centre in between these is the painting The Virgin Mary on the Throne between Seven Angels, by an unknown artist. It was commissioned by Fr Antonio Lo Duca in Venice in 1543. The Blessed Virgin is portrayed with the Holy Child suckling at her breast (this representation is known as the Madonna of Milk). She is crowned by the Archangels Michael and Gabriel. The seven angels represent the Angelic Principalities, and each hold a scroll indicating his duties. In the corners are the prophets David and Isaiah. The sculpted surround, featuring angels and cherubs in a gloria, is by Bernardino Ludovisi.

There is a door, now restored, below the painting which gave access to the choir from the monastery after 1867 when the main altar was moved. Directly above the door is an enshrined copy of a small sculpture of Saint Bruno by Michel-Ange Slodtz, made for St Peter's in 1744 and moved here. The vaults in the apse and presbyterium were frescoed by Daniele Seyter; the motif in the apse is The Assumption of the Virgin Mary, and in the main vault is The Virtues.

Before the altar on the left hand side are two doors; the further one leads to the sacristy, and the nearer one to the Cybo Chapel. To the left of the chapel door is The Baptism of Jesus by Carlo Maratta, painted in 1697 for St Peter's and moved here after his death in 1713. This was one of the first paintings moved here by Pope Benedict XIII. Jesus Christ and St John the Baptist are shown surrounded by angels in a painting of very high quality.

To the left of the above, at the near end of the left hand side wall of the presbyterium, is The Death of Anania and Saphira by Cristoforo Roncalli, known as Il Pomarancio and not to be confused with the more famous Niccolò Circignani. This was also painted for St Peter's, in 1604. The painting shows St Peter reprimanding Ananias and Sapphira, who had lied to the early Christian community at Jerusalem in order to keep some of the money they had earned by selling their earthly possessions (Acts of the Apostles). Sapphira is shown as she is dying - God's punishment - while Ananias is being carried to his grave in the background.

Finally, a new high altar was recently placed in the body of the presbyterium, replacing the former altar for parish Masses. Most (but not all) churches in Rome with parochial obligations now have two main altars, to allow for Mass to be said facing the people. This was a liturgical innovation that followed the Second Vatican Council of the Church (although not authorized by that council). On the front of this new altar is a bronze relief panel of The Deposition from the Cross by Umberto Mastroianni in 1928. The sculptor later turned towards a style more abstract and futuristic than the figurative sculpture shown here.

Cybo Chapel[]

The Chapel of Relics, also known as the Cybo Chapel after the founder Camillo Cardinal Cybo, is accessed to the left of the presbyterium. It has a narrow rectangular transverse antechamber leading into the chapel itself, and was built in 1742 to hold relics of martyrs connected to the building of the Baths of Diocletian. Cardinal Cybo also donated four precious relics of the Western Doctors of the Church: SS Jerome, Ambrose, Augustine and Gregory. Among the martyrs some names have been preserved, such as SS Cyriac, Largus, Smaragdus and Maximus the Centurion. By tradition, there are relics of 730 martyrs here in total. The chapel was decorated by Niccolò Ricciolini, a pupil of Maratta.

Sacristy and Carthusian Choir[]

The sacristy has a barrel vault, and sumptuous decorations from the 18th century. It is a long narrow room, and two doors in the right hand wall lead into the fomer sacristy. This was first designed by Michelangelo, and later altered when Pope Benedict XIII directed that the Carthusian monks should no longer use the Vanvitelli choir in the presbyterium. This was because the latter was too public a place for an enclosed eremitic order of monks. So, in 1727 the former sacristy was consecrated as the Chapel of the Epiphany and functioned as the new Carthusian Choir. The monks used it until 1867, when they moved the choir back to the apse (except for winter, when the church would be too cold).

Just previous to this change of use, the room had been decorated lavishly in a late Baroque style by an artist thought to be Luigi Garzi from Pistoia (1653-1721). Later were added some scenes from the life of St Bruno; the ceiling fresco shows his apotheosis.

Music[]

The church is an important musical venue. There are three organists and a schola cantorum or choir, and they are good enough to tour to prestigious events elsewhere. The choir contains boys and adults.

At present, musical activities are co-ordinated with ARAMUS or the Associazione Romana Arte Musica, the director of which is Osvaldo Guidotti; see their website for details of events and recordings of their work.

The choir performs during the main parish Mass on Sunday, at 12:00.

Access[]

The church is open (parish website, dated January 2018):

7:30 to 19:00 (19:30 on Sundays and Solemnities).

HOWEVER, the Diocese in May 2018 advises that the opening times are 7:00 to 18:30 daily. This may be owing to the parish website not being updated, so be warned of the possible earlier closing.

Liturgy[]

Mass is celebrated (parish website, dated January 2018):

Weekdays 8:00, 18:30;

Sundays and Solemnities 8:00, 10:30, 12:00 (main Mass), 18:00 and 19:00.

The last Sunday Mass is in Latin American Spanish, and in the past has apparently only been celebrated if there is a group which wants it.

Visitors are expected not to wander about the church during Mass.

External links[]

Parish website (has many images; there is an English language version.)

"De Alvariis" gallery on Flickr -exterior

"De Alvariis" gallery on Flickr -interior

"Romeartlover" web-page with 18th century Vasi engraving

Roma SPQR web-page with gallery

Youtube video of solar transit