Santa Maria in Domnica is a parish and titular church built in the 10th century, having also the dignity of a minor basilica. The postal address is Via della Navicella 10 in the rione Celio (the historic rione Campitelli). Pictures of the church at Wikimedia Commons are here. There is an English Wikipedia article here.

Name[]

The dedication is to the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Historically the church has also been known as Santa Maria alla Navicella, and the official diocesan web-page and the parish web-site now combine the two names as Santa Maria in Domnica alla Navicella. However, the cardinalate title remains Santa Maria in Domnica.

History[]

Ancient times[]

The church stands on the crown of the Caelian Hill, and several streets converged here anciently. The most interesting of these routes was the one now delineated by the Clivus Scauri and Via di San Stefano Rotondo. This is a section of a very ancient Stone Age trackway that ran from the lowest fording point on the Tiber near Santa Maria in Cosmedin, along the foot of the Palatine and so eastwards, and so can be regarded as the oldest human artefact in the city.

In Imperial times, when the Caelian hill was completely built over, there were several sets of barracks in the neighbourhood. The site of the church was over the north-eastern wing of the barracks of the so-called "Fifth Cohort of the Vigiles", the main part of which was on the other side of the driveway to the Villa Celimontana. There are two inscriptions confirming the identification preserved at the villa, although no remains of the buildings are now visible outside the church's crypt.

The vigiles were a para-military outfit the main function of which was in fire-fighting. They also provided a first-call police service in response to burglary and individual acts of violence, although major crimes and civil disorder were dealt with by other law-enforcement agencies.

There was a large population of plebs living in multi-storey tenaments or insulae down the slope towards the Colosseum, although the crest of the hill had patrician villas as well as the barracks. An example of the former can be visited under the nearby church of Santi Giovanni e Paolo.

Dominica[]

The foundation of the church is completely undocumented and its first documentary reference is only in 799, when Pope Leo III (795-816) is recorded as establishing the cardinalate title and also giving tapestries and altar decorations to the church. The reference reads: Ecclesia sanctae Dei genitricis quae vocatur Dominica. The word Dominica is a Latin feminine adjective dependent on ecclesia, meaning "pertaining to a lord or lady". On the face of it, it seems to indicate that the church was sponsored by the emperor or his family, or by the Imperial governor in the city.

Scholarly speculation on the name has gone on for centuries. One unfortunate influence has been the maliciously forged legend of the Donation of Constantine, alleging that that emperor entrusted the secular government of the city to the pope and then left him to it. In reality, the citizens regarded themselves as part of the Roman Empire, ruled ultimately by its emperor at Constantinople, until the 9th century. (Modern, tendentious scholarly terminology referring to something called the "Byzantine Empire" before then would have been nonsensical to the people at the time.) So, in 799 ordinary Romans would have regarded Dominica as something to do with the Imperial government. (It also meant "belonging to the Lord God", but then all churches did.)

Cyriaca?[]

The traditional foundation myth suggested that the church might have originated in the 3rd century as a meeting-place for some of the first Christians of Rome. However the subject of where and how these Christians worshipped is now a controverted one, because one and a half centuries of archaeological activity has not managed to locate a single unambiguous "house church". The tituli or early parish churches begin to be documented in the 4th century, and this church was not one of them. Rather, it began life as a diaconia or centre for charitable activities.

A further twist to the myth alleges that the original place of worship was owned by a Greek lady named Cyriaca. This is because the Greek Kuriaka, meaning 'belonging to the Lord', translates into Latin as dominica, hence the church's name. Further, Cyriaca's family catacomb cemetery was where the basilica San Lorenzo fuori le Mura now stands, and it was she who arranged the burial of St Lawrence, deacon and martyr. The legend of St Lawrence described him as handing out alms to poor people at the diaconia here.

None of this is now regarded as historical.

Foundation[]

Anything that we can say about the foundation of the church depends on two questions: When were the barracks of the vigiles abandoned? When were the church's diaconiae set up?

Under the sanctuary of the present church was discovered the foundations of an ancient building which is regarded as part of the barracks, and which has exactly the same alignment as the church. If the identification is correct (the structure aligns in turn with the known remains of the barracks in the Villa Celimontana next door, but this is not conclusive evidence for identification), then we can surmise that the church's site as part of the barracks remained the property of the Imperial government until the 7th century, under the authority of the dux or military governor resident at the old emperor's palace on the Palatine.

The system of diaconiae set up by the Church in the city was in response to the inability of the secular government to continue social services for the citizens. This was especially serious in the case of the annona or free distribution of food-grain, which faded away in the 5th century. The number of diaconiae multiplied in the 6th century, and it is thought that the one here was founded when the premises became available in the early 7th.

Considering the known case of Santa Maria in Via Lata, it is surmised that the original institution was housed in a set of rooms comprising working areas, residential accommodation for monks in charge and a small chapel. It is very likely that the diaconia was staffed by monks forming a small monastery, and that these might have been of the Byzantine rite. There were many monasteries of refugee monks from the eastern Mediterranean established on Rome's hills in the later 7th century, and these flourished until fading away in the 10th.

Vineyards[]

Something very important happened on the Caelian and Rome's other hills in this obscure period in the 6th and 7th century, which has been almost entirely ignored by historical scholarship. The urban landscape became vineyards.

When the aqueducts collapsed which supplied water to the residents of the hills, a process beginning in the 5th century, the only ones who could continue to live there were those who could access well-water. The digging and maintenance of deep wells was beyond the capabilities of ordinary individuals, so these moved downslope to live in the valleys and next to the river. This was the settlement pattern in the early Middle Ages. The hills were then left to monasteries, which had the funds and application to dig wells for themselves.

The citizens then had to source their water from the river, or from wells in the valley bottoms dug through deep layers of ancient detritus. If they did not want to risk an early death, they would refrain from drinking it if possible and rely on wine instead.

The result of the demand for safe drink was that the hills were mostly converted to vineyards. The monks of the monasteries must have organized this enormous engineering enterprise, which is undocumented. In the case of the Caelian, it meant converting a closely-packed multi-storey neighbourhood into open ground for vines, which must have been enormously hard and dangerous work. The debris that resulted seems to have been mostly dumped in the valley leading down to the Roman Forum, raising the ground level there substantially.

Carolingian basilica[]

By 817 the diaconia complex had fallen into serious disrepair, so Pope Paschal I had it rebuilt in the early Christian revival style of the Carolingian Renaissance. Like other churches built by the same pope, Santa Cecilia in Trastevere and Santa Prassede, the architecture of Santa Maria in Domnica was meant to hark back to the early days of the Christian church as a public institution as expressed in the form of the classic basilica such as Old St. Peter's. However, one feature which dates the church is the presence of subsidiary apses at the ends of the side aisles, as by the 9th century the former strict restriction of one altar per church was being relaxed. Churches were now being provided with side chapels.

Middle Ages[]

Unlike other nearby monasteries the one here did not survive the 10th century, when the Eastern monks were replaced in the city by Benedictines. The latter then maliciously pretended that they had been the monks at Rome since the late 6th century, and the archives of the Eastern monasteries were destroyed as part of this airbrushing of Rome's monastic history. The main motivation for this was the bitter hostility that arose between the churches of Rome and Constantinople that led to the Great Schism in 1054, and the result was a disaster for the historical record of ecclesiastical events between the 6th and 10th centuries in Rome.

In the earlier part of the Middle Ages the diaconia continued to function, being run by a small college of secular priests. In the 12th century the superior was referred to as an "archdeacon", which was either an honorific or an indication that he was in charge of other similar institutions being run by the Diocese. Back then, few people lived on the Caelian Hill apart from monastics, but the main road from the Lateran to the Tiber quays passed by here before running down the Clivo di Scauro. As a result, the church saw a steady flow of pilgrims and the diaconia had probably been mainly catering for them. However, by the start of the 14th century the college of priests had dwindled to two.

In 1340 the Diocese finally gave up and a small monastery of the Olivetan Benedictines was established here, although they were to open their main establishment at Santa Francesca Romana in 1351.

[]

The only major structural additions to the church in its history were in 1514 by its titular Cardinal Giovanni de' Medici, who later became Pope Leo X (1513-1521). The architect was Andrea Sansovino. The most noticeable results of this restoration were the creation of a portico for the façade of the church and the insertion of a carved wooden interior ceiling (the roof would have been open beforehand). Also, it is thought that the church's original confessio or semi-circular passageway crypt under the sanctuary was filled in then and the side windows of the nave were made rectangular. Also, the original schola cantorum in front of the altar was smashed up and removed -bits of it found their way into the fill of the crypt, where they were discovered in the 20th century.

The restoration also involved the siting of a stone sculpture of a small boat or navicella, that is now located as part of the fountain in front of the church. It is this sculpture that lends its name not only to the street and piazza that the church is located on, but also to the alternative name of the church itself: Santa Maria alla Navicella, or "St. Mary by the Boat." Originally, the sculpture was by the left hand side of the portico.

It used to be thought that this sculpture was an ancient votive offering, but it has now been demonstrated that it is 16th century and so would have been carved when the church was restored. The pretty pebble mosaic inside is certainly of that period. If the sculpture was based on an ancient prototype now lost, the latter would probably have been an allusion to the expatriate status of the legionary soldiers who might have commissioned it, in the barracks of the Castra Peregrina across the road now under the church of Santo Stefano Rotondo al Celio. An attractive hypothesis is that bits of a broken boat sculpture were found locally in the early 16th century, which were used as a model of the present work before being thrown away.

17th and 18th centuries[]

Over the next five hundred years the church has had several renovations, but none of these much altered the form of the structure.

In 1565, work started on providing a new ceiling, which means that the one installed fifty years earlier must have been damaged somehow (or badly made). The work took twenty years, and resulted in the present impressive ceiling (although the colouring is 19th century). The patron was Cardinal Ferdinando de' Medici, who held the title despite being a layman. The frieze below the ceiling cornice, displaying lions with putti, was also part of this project.

The Olivetans gave up the monastery at the end of the 16th century, and Pope Paul V (1605-21) put the church in charge of prebendary canons. These were secular priests who were paid a salary to attend to liturgical functions, and it is a good guess that they did not live on site. In fact, throughout the 17th century there seems to have been little if any artistic activity here and the Baroque era rather passed the church by. In 1686 there was some sort of restoration, but what this amounted to is not documented.

Pope Clement XI (1700-21) had the portico decorated and the apse mosaic restored, and in 1725 Pope Benedict XIII re-consecrated the high altar after the sanctuary was re-fitted. The architect of this latter work was Tommaso Mattei.

In 1734 the convent was transferred to Basilian monks of the Melkite rite, and the church was to be Eastern-rite for the next two hundred years.

19th century[]

In 1822, Pope Pius VII instigated a restoration under the patronage of Cardinal Tommaso Riario Sforza, during which the two large windows in the façade were made rectangular to match those in the side walls. The ceiling was also painted in the colour scheme which it now has.

The little convent was suppressed in 1873, and the property expropriated by the Italian government together with all the other convents in the city. The Melkite expatriate community remained in possession of the church, but apparently did not make much use of it and at the start of the 20th century it was described as "seldom open".

Chandlery writing in 1903 had this to say: "The church stands in a picturesque spot on the highest part of the Coelian hill, commanding charming views of the Alban and Sabine hills and of the Roman Campagna with its long lines of aqueducts stretching away into the distance". This view was already being destroyed by suburban development at the time he wrote.

The altars and the portico were renovated in 1881. As an ancient building the church was lucky to escape the ideologically motivated "restorers" of the next fifty years, unlike Santa Maria in Cosmedin for example, and so has kept its late Renaissance façade.

Parish[]

After the Lateran Treaty of 1929 the premises were formally leased back to the Diocese, and in 1932 the church was declared to be the parish church for the rione Celio. Also, the road junction was improved in the previous year and a piazza laid out in front of the church. The boat sculpture was moved to outside the main entrance to form a fountain and its axis rotated, so that it is now parallel to the church façade instead of perpendicular to it as previously.

Oddly, the church lacked an organ and this is because the Eastern rites usually do not use one. Many of them, such as the Melkite, use microtonal music so an organ would be useless anyway. An instrument was obtained for the parish from the chapel of the nearby Military Hospital, which had been assembled in 1910. When it was brought here, it was installed over the main entrance.

The Melkite expatriates, having thus lost their church, eventually settled at Santa Maria in Cosmedin.

Serious problems emerged in the mid 20th century with the stability of the structure, so in 1957 the apse of the church was underpinned and a new crypt constructed. This work was by Ildo Avetto, under the sponsorship of Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani.

For a year from 1988 there was a cleaning and restoration of stone sculptures and architectural elements, and provision of new furnishings for the sanctuary.

In 2004, administration of the parish was entrusted to the Priestly Fraternity of the Missionaries of St Charles Borromeo (FSCB). They have overseen another cleaning and restoration of the façade as well as work on the side aisles.

At present, the rather small parish community is trying to offset the cost of maintaining the building by making it available to the weekend Centro storico church marriage circuit, which means that trying to visit on a Saturday is often not a good idea.

Cardinalate[]

The church remains a cardinal diaconate.

Among the church's titulars were Popes Stephen IX, Gregory VII and Clement VII; Tommaso and Giovanni Battista of the Orsini family, Innocenzo Cardinal Cybo, Federico Borromeo senior (died 1589) and Tommaso Riario Sforza.

The latest holder of the title was William Joseph Levada, who held the dignity of cardinal priest pro hac vice and who died in 2019.

Exterior[]

Layout and fabric[]

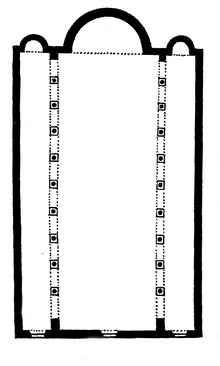

The plan of the church is very straightforward, being a rectangular basilica with aisles and a wide external segmental main apse with a conch. The aisles have apses, too. There is no structurally distinct sanctuary apart from the main apse.

The exterior walls are rendered in a pale yellowish grey, and the roofs are pitched and tiled.

There is no proper campanile as such, but a small bellcote is perched on the near end of the right hand aisle which was built in 1714. The design of this is in the form of a little triumphal arch, with one arched opening crowned by a triangular pediment having a broken cornice. A heraldic shield occupies the tympanum, and flanking the arch are pendant panels with tassels. It contains one bell, with an inscription giving the year of manufacture as 1288.

Façade[]

The flat-roofed external portico was added by Sansovino in 1513. He was inspired by the work of Bramante, and provided a work of high enough quality for it to have been erroneously attributed to Raphael in the past.

It has a sober and dignified row of five identical arches with two more on the sides, and these have Tuscan Doric imposts. In between the arches and on the portico's corners are six matching Doric pilasters which support an entablature, and arch piers and pilasters are in travertine. Above the entablature the flat roof sits on an additional low attic plinth.

The archivolts of the arches are molded, and bear lions' masks on their keystones.

Behind the portico, the gabled nave façade rises to a triangular pediment. It has a row of three windows, the central one being circular in a dished frame and with geometric fenestration involving a circle and two squares. The other two windows are vertical rectangles with stone frames, and identical windows are provided in the aisle and upper nave walls. The ones here were altered to match the latter in the 19th century

The frieze below the pediment bears a dedicatory inscription: Divae Virginis templum in Domnica, a dirutum Io[annes] Medices Diac[onus] Card[inalis] instauravit. The pediment tympanum contains the coat-of-arms of Pope Innocent VIII in the middle and those of Cardinals Giovanni de' Medici (the future Pope Leo X) and Ferdinando de' Medici to each side.

Monastery[]

To the right of the church is the small, originally Olivetan monastery, which contains a mediaeval brick tower. However, the street frontage and much of the rest of it looks as if it were rebuilt in modern times, and is ugly and functional.

Interior[]

Santa Maria in Domenica

Layout[]

The church has a central nave with side aisles, these ending in a triple apse which is an architectural style traditionally regarded as Byzantine. The central apse is proportionally rather wide. The side aisles are very narrow.

There are no external side chapels. Under the sanctuary is a semi-circular passage crypt, which is modern.

[]

Unusually, the nave arcades run right up to the back wall of the church containing the three apses, and so there is no triumphal arch into the sanctuary. The arcades have eighteen ancient granite columns, all with white marble Corinthian capitals of which most are spolia from ancient buildings. The capitals differ in design, and repay close inspection -there has been some argument as to whether all are genuinely ancient, or whether some were carved for the 9th century rebuilding. Sixteen of the columns are in grey granite, and two in pink.

The clerestory of the central nave is lit by five rectangular windows on each side, and its upper side walls have 19th century fresco work (now badly faded) executed to resemble marble and stucco decorations. These windows used to be round-headed, but were altered in the 16th century renovation.

This 19th century fresco scheme on the side walls includes Marian symbols echoing those in the ceiling above. The artists were Alessandro Mantovani, Giovanni Brunelli and Luigi Roncati and the work was finished in 1876.

High up on the nave walls, just below the ceiling, is a painted frieze in a Renaissance Classicizing grotesque style executed by Pierino del Vaga to a design by Giulio Romano, a student of Raphael. It displays erotes giving drink to lions, and is rather charming.

The side aisles are cross-vaulted. The floor was re-laid in 1957, and contains the heraldry of Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani.

The central round window over the organ in the counterfaçade has recently been given stained glass depicting the Dove of the Holy Spirit.

Ceiling[]

The coffered, carved and painted flat wooden main ceiling was provided by Cardinal Ferdinand de Medici in 1566, and so has the coat-of-arms of the Medici family in the large central panel: Or, five balls in orle gules, in chief a larger ball of the arms of France being azure, three fleurs-de-lis or. The balls are unusual in heraldry, and the carving depicts them as red spheres. The motto reads: Ferdinandus Medices Card[inalis], templi ornamento memoriaeq[ue] Leonis X renovadae fecit, Pii V anno I. ("Ferdinand de' Medici for the decoration of the temple and the renewal of the memory of Leo X did this, in the first year of Pius V").

Pierino del Baga was also the artist responsible, and again took the design from Giulio Romano.

There are two other large main panels, one depicting Noah's Ark with the dove returning and the text Spes nostra salve. This means "Our hope, hail" and is a line from the Marian hymn Salve regina. Thus, Our Lady is being symbolized by the Ark. The other panel shows the Barque of St Peter, or the Church symbolized by a boat. The ship is actually carrying a round Classical temple, with an open door through which the Blessed Sacrament can be seen displayed in a monstrance. The text on the entablature frieze reads Dominus firmamentum.

The symbols in the smaller square coffers surrounding these panels display various Marian symbols, many of them taken from the Litany of Our Lady.

The ceiling was repainted in 1822.

Sanctuary[]

Because of the lack of a transept, the sanctuary intrudes into the nave. It is raised above a crypt accessed by two side staircases, and is approached by seven new white marble steps which occupy the next to last bay of the nave. The last bay of the nave is occupied by the floor in front of the free-standing 18th century altar, which has no aedicule. The frontal is revetted in red jasper, and has a heraldic shield displaying a coronetted double-headed eagle.

The steps were finished for 2000, and with them were also provided a new baptismal font to the left and an ambo standing on a plinth in the stairs to the right. These are interesting and effective work of modern religious art. The font is an octagonal cup in white marble inlaid with porphyry, on a ribbed column inlaid with green serpentine. The ambo features a U-shaped bronze grating of irregular pattern evoking flying angels.

The sanctuary apse is flanked by a pair of porphyry columns with Ionic capitals which support the triumphal arch. This has no distinct archivolt, but instead the mosaic work in the conch is of one piece with that on the far wall containing the apse. To the right of the right hand column is a wall aumbry or holy-oil cupboard in polychrome marble work.

The curve of the apse wall has three large fresco panels separated by painted trompe-l'oeil columns matching those of the arch. This work is by Lazzaro Baldi, of the late 17th century, and depict scenes associated with the foundation legend of the church. The central one shows St Lawrence Washing the Feet of the Poor, to the left is The Healing of St Cyriaca and to the right, St Lawrence Distributes Bread to the Poor. The two narrower side panels show, to the left St Zechariah with the Infant St John the Baptist, and to the right An Angel Inspires St John the Evangelist to Write His Gospel.

The porphyry columns mentioned support a U-shaped marble cornice running round the apse and separating the frescoes from the mosaics above. It bears an inscription commemorating the restoration by Cardinal Giovanni de' Medici.

Mosaics[]

The apse mosaics are from the 9th century, commissioned by Pope Paschal I (817-824) and known to have been restored on the orders of Pope Clement XI .

In the vault of the conch of the central apse Pope Paschal is shown kneeling at the feet of the Blessed Virgin enthroned, and this is one of the earliest examples of a mosaic where the Madonna is in the centre of the composition. The choice of motif should be seen as a protest against iconoclasm, which was still rampant in the Byzantine Empire at the time, and both the Byzantine style of the mosaics and the Eastern elements in the architecture indicates the Greek exiles were involved when the church was built and decorated. Notice that the Holy Father has a square halo, which tells us that he was still alive when the mosaic was made.

Our Lady is depicted seated on a throne with a scarlet cushion, and with her feet on a yellow rug with a crimson line along its border. She is dressed in a blue robe, and is holding the Christ Child. The latter is represented as a miniature adult, which is a typical motif of the Byzantine style, and also typical is the napkin that Our Lady is holding as if she were a Byzantine princess. She is flanked on either side by hosts of angels, and throne and angels stand on a flowery meadow. Below the composition is a dedicatory inscription, and in the intrados of the arch is a monogram that spells out PASCHAL.

The inscription reads: Ista Domus pridem fuerat confracta ruinis nunc rutilat iugiter variis decorata metallis et Deus ecce suus. Splendet ceu Phoebus [Venus in the morning] in orbe qui post furva fugans tetrae velamina noctis. Virgo Maria tibi Paschalis praesul honestus condidit hanc aulam laetus per saecla manendam. ("This house was once broken down in ruins, now it glistens for all time being decorated in various metals and behold God belongs to it. It shines like Phoebus in the world after the foul covering of horrible night flees. Virgin Mary, for you Paschal the trustworthy leader joyfully founds this house to remain for ever. ")

Above the apse the triumphal arch wall has a register showing Christ sitting on a rainbow in a mandorla and being venerated by a pair of angels, with the twelve Apostles approaching from the sides. Below, flanking the conch of the apse are two figures now thought to be Moses and Elijah. The identification of the latter two has been controversial, and on a notice that used to be outside the church they were said to be SS Peter and Paul. This is very unlikely, as they do not resemble the Apostles who are already depicted above. Another alternative suggestion is that they are meant to be SS John the Baptist and John the Evangelist.

Side aisles[]

The cross-vaulting of the side aisles is undecorated and whitewashed. At the end of each aisle is a small apse with a conch, the right hand one now being the Blessed Sacrament Chapel and the left, the Chapel of the Sacred Heart. Both chapels have fresco work executed by Gisberto Ceracchini in 1930, which unfortunately has not kept well.

The left hand chapel has a modern statue of the Sacred Heart by Giovanni Prini, and angels in fresco represented as holding drapery (the technical term for this is reggicortina). The conch contains the Dove of the Holy Spirit.

The right hand chapel contains the Blessed Sacrament in a tabernacle of black marble, red jasper and alabaster with a gilded bronze door having a relief of the Risen Christ. The dedication seems to be to Our Lady of Sorrows, and a trio of fresco angels is depicted putting up a flower garland around an icon of her on the wall. Other angels are depicted standing to the sides and looking on. The apse conch contains the Dove again, but this has faded badly.

At the end of the right aisle is a memorial to Antonia of Luxembourg (died 1954), last crown princess of Bavaria . This is a marble tablet with an inscription in archaic style imitating those found in the catacombs. Also shown are the heraldic shields of the Wittelsbachs, the Royal House of Bavaria (which she married into) and the Grand Ducal House of Luxembourg (of which she was a princess). These flank a cameo-style portrait.

The baptistry used to be at the near end of the left hand aisle, with a modern fresco of the Baptism of Christ by Luca Brandi. The baptismal font is now in front of the sanctuary.

Crypt[]

The semi-annular crypt under the sanctuary was installed in 1957 when the apse was underpinned. When it was dug out evidence of a wing of the ancient barracks of the Vigiles was found, which is 3rd century. This edifice was the putative first accommodation of the diaconia, but no evidence of Christian activity was found in it.

The crypt now has ancient Roman sarcophagi, fragments of 9th century plutei and a 17th century altar. A modern sculpture of Christ in Gethsemane by Prini was installed here.

The plutei were carved marble screen-slabs, which here show vine-scroll decoration. It is thought that they belonged to the original schola cantorum, or enclosure for singers and clerics, which stood in front of the altar provided by Pope Paschal. See San Clemente for a surviving example. The one here was smashed up and thrown away in the 16th century restoration.

Access[]

At the time of writing (November, 2023), the church is only open on weekdays at 19:00 for Mass and on Sundays at 11.00 and 19.00 .

External links[]

"De Alvariis" gallery on Flickr -exterior

"De Alvariis" gallery on Flickr -interior

"Settemuse" web-page with photos

Template:Commons

Bibliography[]

Beny, Roloff, and Peter Gunn: The Churches of Rome. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1981.

Bishop, William Warner: Roman Church Mosaics of the First Nine Centuries with Especial Regard to their Positions in the Churches 1906, pp 251-281.

Bombi, Barbara: L’Ordine Teutonico nell’Italia Central: La Casa Romana dell'Ordine e L'Ufficio del Procuratore Generale. L'Ordine Teutonico nel Mediterraneo: Atti del Convegno Internazionale di Studio, Torre Alemanna, Cerignola, Mesagne, Lecce, 2003.

Cruickshank, J. W., and A. M: Christian Rome. London: G.Richards, 1911.

Elchberg, Michael: Die navicella vor S. Maria in Domnica auf dem Caelius. Romisches Jahrbuch der Biblioteca Hertzianai 30, 1995, pp 308-14.

Englen, Alia: Restauri d’arte e Giubileo: Gli Interventi della Soprintendenza per i Beni Artistici e Storici di Roma nel Piano per Il Grande Giubileo del 2000. Electa Napoli, 2001.

Forbes, S. Russell: Rambles in Rome; An Archaeological and Historical Guide to the Museums, Galleries, Villas, Churches, and Antiquities of Rome and the Campagna. London: T. Nelson and sons, 1882.

Krautheimer, R. Corpus basilicarum christianarum Romae.2 vol. Vatican City, 1937-1977.

Lanciani, Rodolfo: Wanderings Through Ancient Roman Churches. London, Constable and Company Ltd, 1925.

Letarouilly, P.M. Edifices de Rome modern, ou, Recueil des palais, maisons, églises, couvents et autres monuments publics et particuliers les plus remarkables de la ville de Rome. Paris, 1856.

Leuker, Tobias: Das Wirken der Medici für die Römisched Kirche Santa Maria in Domnica im 16. Jahrhundert. Römisches Jahrbuch der Bibliotheca Hertziana 34 (2001/2002): 185-99.

Magister, Sara: I restauri del Raguzzini nelle chiese romane e un caso inedito di collaborazione con Tommaso Mattei Alessandro Specchi e Pier Leone 'Ghezzi in Santa Maria in Domnica. L’arte per I giubilei e tra I giubilei del Settecento: arciconfraternite, cheise, artisti. 1999.

Mâle, Émile: The Early Churches of Rome. Chicago: Quadrangle Books Inc., 1960.

McClendon, Charles B. The Origins of Medieval Architecture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005.

Parker, John Henry: Mediæval Church and Altar decorations in Rome, and Mosaic Pictures in Chronological order. Oxford: J. Parker, 1876.

Sharp, Mary: A Guide to the Churches of Rome. Philadelphia: Chilton Books,1966.

Sundell, Michael G: Mosaics in the Eternal City. The Catholic Historical Review. 95. No. 1 (2009): pp 88-9.

Webb, Matilda: The Churches and Catacombs of Early Christian Rome: A Comprehensive Guide. Portland: Sussex Academic Press, 2001.